Find the motivation for routine physical activity

This is an excerpt from Applying Music in Exercise and Sport by Costas I Karageorghis.

Music as a Prime

To overcome the almost overwhelming array of potentially negative external forces that inhibit progress toward their goals, people require tight routines, considerable self-discipline, and regular social support. Music can play a critical role by forming part of a routine and creating a mind-set associated with exercise and physical activity. Research shows that music can have a priming effect, meaning that it can activate the mind automatically (i.e., without conscious effort) and increase the motivation to exercise and take part in physical activity (e.g., Goerlich et al., 2012; Loizou & Karageorghis, 2015; Loizou, Karageorghis, & Bishop, 2014). Music can help elevate us; it can be a bridge to our higher purposes and goals.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, priming is a psychological technique popularized and refined by people in marketing. Back in the mid-1950s, market researcher James Vicary contrived an intriguing experiment in which the phrases Drink Coca-Cola and Eat popcorn were flashed on movie screens for just 0.03 seconds during the first half of movies (Vicary, 1957, cited in Radford, 2007). The viewers were not consciously aware of these visual primes (they appeared for too short a time to be registered), but they apparently led to an 18 percent increase in sales of Coca-Cola, and a whopping 58 percent increase in sales of popcorn during the interval.

Considerable controversy surrounded Vicary's claims and persists to the present day, but U.S. government legislators were quick to prevent companies from using such techniques to promote the purchase of consumer products. Despite the ban, similar techniques - now applied with a staggering degree of sophistication - are used routinely by advertisers. Apparently, the priming police have no teeth!

Research has demonstrated that people are largely unaware of the processes underlying their perceptions, pursuits, and behaviors (Levesque & Pelletier, 2003). Given that such processes play a pivotal role in health-related behaviors, taking some control over them through the measured application of pre-exercise music can create a pattern of thoughts and feelings that lead to the initiation of exercise-related behaviors. Music activates the emotional and movement-related segments of the brain such as the amygdala, temporal lobe, and cerebellum (see figure 2.2 in chapter 2) and can therefore greatly facilitate the mental preparation for exercise.

Scientists maintain that music has a particularly strong influence on the brain's unconscious processes (e.g., Levitin & Tirovolas, 2009; Scherer & Zentner, 2001). As noted in chapter 2, studies investigating high-intensity exercise have shown that well-selected music can enhance how people generally feel (affect), although it has little influence on their perceived exertion (RPE; Hutchinson & Karageorghis, 2013; Karageorghis et al. 2009). To a degree, such findings support the notion that the brain processes music at a subcortical, or automatic, level without conscious effort. It is precisely this apparent lack of a need for conscious processing that can make music an ideal form of prime for people who want to create an exercise habit. We do not have to think very much for music to influence our behaviors or feelings.

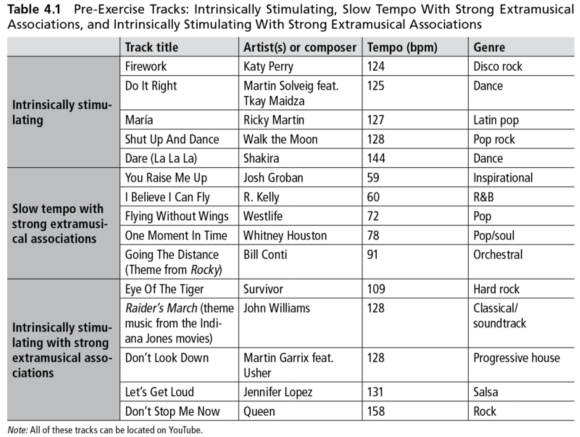

As discussed in chapter 2, both stimulative and calming music can prepare people mentally for exercise. Stimulating music can promote the entrainment of brain waves, the heartbeat, and the breathing rate, whereas calming music with strong extramusical associations can conjure the right type of mental imagery or thought processes (e.g., heroic images, thoughts of overcoming adversity, motion-related thoughts). Table 4.1 lists examples of musical works that function particularly well as preparatory tracks for physical activity programs. The tracks are arranged in three categories: those that are intrinsically stimulating (i.e., upbeat and energetic), those that are relatively slow in tempo but have strong extramusical associations, and those that both are stimulating and have strong extramusical associations.

Situations and circumstances will determine which category in table 4.1 you might wish to dip into for a pre-exercise track (consider also the theoretical model in figure 2.8). The first category, intrinsically stimulating, works particularly well for diverse groups of exercisers who do not necessarily have common cultural reference points (e.g., a physiotherapy rehabilitation class with a mix of age groups and ethnicities).

The second category, slow tempo with strong extramusical associations, would serve individuals or small groups of exercisers with common cultural reference points (e.g., they enjoy similar movies, have similar musical tastes, frequent the same social venues). The key consideration is that the exerciser(s) do not require a great deal of bodily activation but more mental stimulation, perhaps as a precursor to engaging in a stretching, yoga, or Pilates session. Older people and introverts tend not to like highly stimulative music; therefore, the second category might be ideal for them. This is a general rule that certainly does not hold in all instances; if you happen to be working with a 74-year-old grandma who's into Led Zeppelin played at high amplitude, you'd better pander to her tastes!

The third category is for individuals or groups with common cultural points of reference who are about to engage in vigorous and demanding physical activity (e.g., a high-intensity run or a step class). Here the goal is to activate or stimulate both the mind and body to a high degree. Younger and more extroverted exercisers tend to report a preference for more stimulative music as well. You might wonder why there is no fourth category of slow-tempo music without extramusical associations (i.e., sedative music). Well, we know from research, and to a certain degree common sense, that such a category has no meaningful role to play in preparing people for exercise (Karageorghis & Priest, 2012a). It can, however, play a role in preparing people for sport (see chapter 7).

Learn more about Applying Music in Exercise and Sport.

More Excerpts From Applying Music in Exercise and SportSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Sample mental health lesson plan of a skills-based approach

- Sample assessment worksheet for the skill of accessing valid and reliable resources

- Help your students overcome what holds them back from making health-promoting choices

- Example of an off-season microcycle

- Modifying lifts

- Screening for multilevel programs in a team environment