Nutrient timing for heat and humidity

This is an excerpt from Performance Nutrition by Krista G Austin,Bob Seebohar.

The body naturally produces heat at rest as a result of breaking down energy stores. During exercise the amount of heat produced is proportional to exercise intensity, and this raises a person's core body temperature. As the brain senses an increase in core temperature, blood flow is increased and taken away from the core of the body. This results in an enhanced cardiac output, which is evidenced by an increased heart rate at rest and during exercise. The blood is distributed to working muscles to facilitate their function by maintaining oxygen delivery and increasing the removal of waste and heat. Blood flow will also increase to the body's surface (skin), where heat is then removed through sweating.

The body uses four different methods—evaporation, convection, radiation, and conduction—to remove heat from the body so that severe hyperthermia (very high increases in body temperature) does not occur. Evaporation removes heat through sweating and is highly dependent on the amount of moisture in the air. In hot, dry conditions sweat is quickly dissipated; as the moisture content of air (i.e., humidity) increases, sweat cannot be readily removed, and less heat can be eliminated through this method. In a hot, dry environment evaporation accounts for up to 90 percent of heat loss. When humidity increases to greater than 50 percent, the body must increase reliance on other methods to remove heat. If this is not feasible, heat will continue to be stored by the body, and exercise intensity and duration will eventually be reduced.

The other means of removing heat is through nonevaporative methods that require an increase in heat loss to the environment or an object that is cooler than the body's temperature. In radiation, heat is given off by one object (the athlete) and is absorbed by the environment or another object that the person is in contact with (e.g., the ground). In convection, heat is lost by a person moving through a current (air or fluid). Conduction is the transfer of heat to another object through touch (e.g., the hand touching a cold surface) and in most situations accounts for very little heat loss.

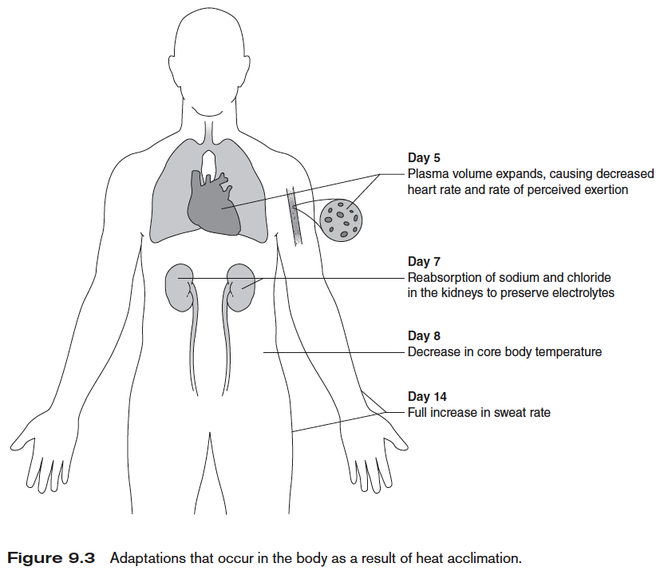

When athletes move from a cool or moderate temperature to a hot environment, proper acclimatization to the heat over a two-week period before competing or training at full volume and intensity is probably the most important thing they can do. Athletes who experience hyperthermia when competing or training in the heat have usually not acclimatized appropriately. Acclimatization can be done by slowly increasing training volume and then intensity and by training at the coolest times of the day. The body's response to acclimatization is depicted in figure 9.3.

During the first five days of heat exposure, the adaptations of a decreased heart rate and perceived exertion to a training bout will occur. This is a result of an increase in plasma volume and the start of an increased retention of electrolytes (primarily sodium) in the sweat and urine. By day 10, core body temperature is decreased as the brain resets and increases sweat rate to compensate during exercise. The full increase in sweat rate is completed by day 14. Complete adaptation is also marked by a significant shift from anaerobic to aerobic metabolism and thus a greater reliance on fat as a fuel source rather than carbohydrate. The increased reliance on fat can be highly attributed to a reduction in strain on the body as a result of increased heat removal through a raised sweat rate, a decreased relative exercise intensity, and a decreased number of muscle fibers needed to perform the same amount of work. Together, these markers are evidence of a complete adaptation to the heat.

Energy and Hydration Needs

Ensuring that an athlete takes in adequate fuel and fluid during exercise in the heat is important to minimize injury and prevent premature fatigue. An athlete moving from a cool or moderate temperature to one that is hot experiences several shifts in metabolism that must be accounted for during training. At rest, RMR is decreased on average by approximately 5 percent. This is attributed to a decreased need to maintain body temperature because the environment helps do this; however, a hot environment can lead to decreased appetite, and as a result athletes need to be careful that they meet their energy needs.

Training in the heat increases de-mands on the body's metabolism in proportion to the increase in environmental heat. With a significant shift toward a more anaerobic metabolism, initial exposure results in increased carbohydrate use and decreased fat utilization; an increased sweat rate also leads to greater fluid losses. This happens because the athlete is working at a higher relative percentage of maximal capacity and because an increase in muscle temperature decreases muscle efficiency. When muscle temperature increases, muscle crossbridges fatigue at a higher rate; thus, the number of muscle fibers recruited over time will need to increase so that work capacity can be sustained. Depending on how well athletes acclimatize to a hot environment, they may or may not improve their reliance on fat as a fuel source. However, with heat acclimation, appropriate fueling and hydration strategies, and body-cooling techniques (e.g., cooling vest, cold showers or baths, hand and feet immersion in cool water, cool towels or ice packs), an athlete should be able to train and perform in such a harsh environment.

Because an athlete's body temperature is higher in warmer environments, the desire to eat can be significantly reduced; thus, it is important for an athlete to identify foods and fluids that taste pleasant at rest and during exercise. It is best to have a wide variety of palatable foods and fluids available and to make part of the recovery meal fluid based. Energy needs can be met through several different means. The types of fluid ingested and the amount of residue a food contains should be considered. The first strategy is to increase the calorie content of fluids used to rehydrate (e.g., meal replacements, carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages, juices, smoothies, iced tea). A second option is to increase low-residue foods eaten as snacks every 30 minutes to an hour in between meals. These foods are easier to digest and do not indicate to the receptors of the stomach that it is full. In addition, less heat is produced as these foods digest, and as a result, this will help control body temperature. Examples of high- and low-residue foods are listed in table 4.1 on page 73-74.

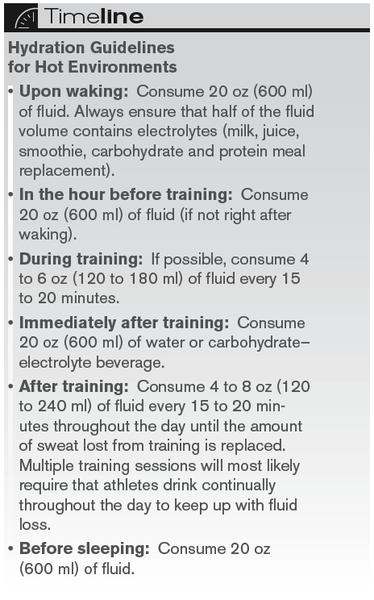

It is not uncommon for fluid loss to exceed the amount able to be taken in during training. Fluid ingestion can considerably improve the body's ability to minimize heat storage by helping to maintain sweat rate and providing a cooling sensation when ingesting fluids that are below body temperature. A timeline for fluid ingestion is important for coping with the heat. The timeline needs to ensure that an athlete enters each training session well hydrated and that hydration begins immediately after training and if possible is also incorporated into training. The temperature of a beverage can significantly influence how palatable it will be to an athlete and how quickly it can absorbed by the body. Cool fluids are best when training in a hot environment; when at rest, fluids that are at room temperature or slightly cooled will be better tolerated. The timeline shows guidelines for maintaining hydration when training in a hot environment.

Learn more about Performance Nutrition.

More Excerpts From Performance NutritionSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Using double inclinometers to assess cervical flexion

- Trunk flexion manual muscle testing

- Using a goniometer to assess shoulder horizontal adduction

- Assessing shoulder flexion with manual muscle testing

- Sample mental health lesson plan of a skills-based approach

- Sample assessment worksheet for the skill of accessing valid and reliable resources