Assessment of nutritional status in clients with COPD

This is an excerpt from Guidelines for Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programs 5th Edition With Web Resource by .

By Ellen Aberegg

Assessment of Nutritional Status

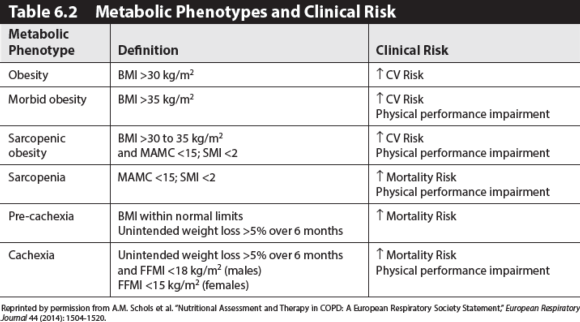

Nutritional status is an important determinant of COPD outcome. Evaluation of nutritional status includes analysis of body composition and diet intake. Nutrient status deemed at risk from these two assessments may require further detailed serum analysis. Schols and others have identified different metabolic phenotypes of COPD that are useful in patient counseling as well as in future clinical trial design. Refer to table 6.2 for an overview of the described phenotypes and health risks.

Body Composition Assessment

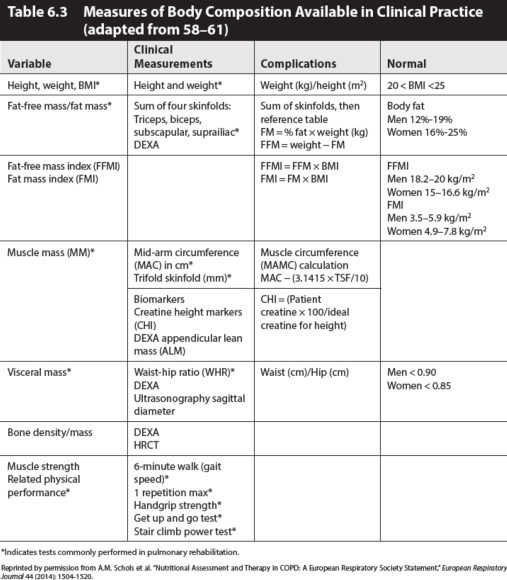

Incorporation of body composition analysis into nutritional assessment has been a major step forward in understanding systemic COPD pathophysiology and nutritional potential. Identification of patients at risk of diminished fat-free mass increases the potential for improvement in clinical outcomes by subsequent appropriate supplementation. Measurements of height and weight, weight history, and specific anthropometric measurements are assessable in most pulmonary rehabilitation settings. The most accurate methods are not suitable for common daily use in pulmonary rehabilitation due to their high cost and time burden. Skinfolds may overestimate FFM, although many studies found no significant difference by method. Clinical indications of each individual will determine the necessity of more expensive or precise serial methods of assessment, particularly in osteoporotic, pre-cachexic, and cachexic patients. See table 6.3 for assessment information.

Training and competency are essential for pulmonary rehabilitation professionals to ensure accuracy and validity of measures. For specific instructions on methods of measurements, see Fitness Professionals Handbook, 2016. Specific anthropometric measures are listed in table 6.3. Calculations of BMI, FFM, FM, FFMI, and FMI are made using standard reference equations. The major shortcoming of the BMI is that the actual composition of body weight is not taken into account: excess body weight may be made up of adipose tissue or muscle hypertrophy, both of which will be judged as “excess mass.” On the other hand, a deficit of BMI may be due to an FFM deficit (sarcopenia) or a mobilization of adipose tissue or both combined. In a study of European Caucasian males and females aged 18 to 98 years, using the 25th and 75th percentiles as cutoffs, Shutz proposed the following FFMI and FMI ranges as normal. The 25th and 75th percentiles correspond well to the cutoff of BMIs of 20 and 25 kg/m2 respectively. Thus, skinfold measures have been demonstrated as an accessible tool for determination of FFM and FM utilizing the Durnin Womersley equation, the Siri equation, or the Jackson-Pollock equations for men and women. Revised equations for obese individuals have been proposed.

Risk increases as FFM decreases, FM increases, involuntary weight loss occurs, or BMI varies high and low from the norm. As these parameters vary along a continuum, four clusters of risk become apparent. Schols identifies these clusters as metabolic phenotypes: obesity and morbidly obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity, normal WNL, plus cachexic and pre-cachexic.

Cachexia and Pre-Cachexia

Cachexia is a complex syndrome frequently present in patients with chronic severe illnesses, including COPD, cancer, and congestive heart failure. Cachexia is associated with increased mortality, impairments in health-related quality of life, and muscle weakness. The clinical phenotype of cachexia ranges from minimal or no weight loss with signs of muscle wasting to severe weight loss with signs of muscle depletion, fatigue, and reduced mobility. The anthropometric measure of FFMI is an indication of risk. An FFMI 2 for men and 2 for women) is a strong predictor of mortality, thus an urgent flag for nutrition intervention. Weight stabilization and gains in FFM will be clear indicators of improvement attainable while the patient is in the pulmonary rehabilitation program. The pre-cachexic patient is in a state of >5% unexplained BW loss over 6 months without measurable deficits in FFM. Nutrition intervention is warranted due to increased risk and weight stabilization and improvement in diet quality will be the indicator of improvement.

Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity

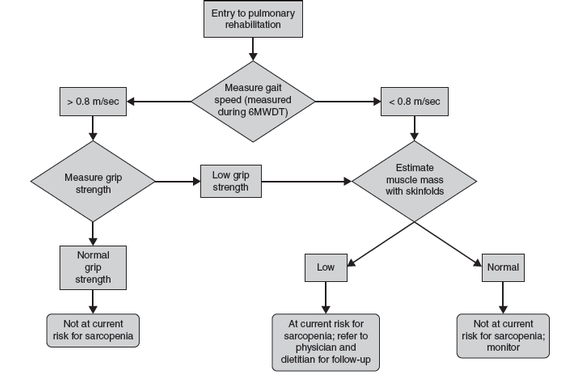

Sarcopenia is a deficit in skeletal muscle, and thus FFM, resulting in weakness. While the clinical relevance of sarcopenia is widely recognized, there is currently no universally accepted definition of the disorder. Sarcopenia may be optimally defined (for the purposes of clinical trial inclusion criteria, as well as epidemiological studies) using a combination of measures of muscle mass and physical performance.

Sarcopenia is prevalent in patients eligible for pulmonary rehabilitation throughout all ranges of BMI. A deficit of FFM may occur regardless of FM status. Schols recommends using appendicular skeletal muscle index (SMI) (appendicular lean mass as measured by DEXA)/height2)

Sarcopenic obese men had the highest risk of all-cause mortality but not CVD mortality. Efforts to promote healthy aging should focus on preventing obesity and maintaining muscle mass. Abdominal obesity seems to have protective effects on physical functioning. Sarcopenia and central adiposity were associated with greater cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. Atkins found that composite anthropometric measure of MAMC and WC is more effective in predicting all-cause mortality than measures of FFMI and FMI. Traditionally, the nutritional interest in COPD, cystic fibrosis (CF), and lung cancer has been on management of weight loss and muscle wasting (cachexia) in advanced disease stages, while obesity was predominantly investigated in relation to onset and progression of asthma and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Obesity has now been identified as a risk factor across all respiratory diseases. Furthermore, combined with aging-induced changes in muscle mass (sarcopenia), the clinical significance of sarcopenic obesity has been highlighted in COPD and lung cancer.

In a large longitudinal study, the Cardiovascular Health Study found that sarcopenic obesity that was characterized using muscle strength was modestly associated with CVD risk. In men with decreased endurance, WC and low muscle mass, as measured using MAMC, were associated with all-cause mortality. Sarcopenia (MAMC ″25.9 cm) and obesity (WC >102 cm) were associated with CVD mortality and all-cause mortality risk, but did not have an excess risk of CVD mortality beyond that associated with sarcopenia or obesity alone. Sarcopenic obesity was more strongly related to non-CVD mortality, independent of inflammation, than CVD mortality. Despite the sarcopenic obese group having the highest risk of mortality, there was no evidence of interaction between sarcopenia and obesity, suggesting that the presence of obesity does not modify the effect of sarcopenia.

Figure 6.1 A suggested algorithm for sarcopenia case finding. Consider comorbidity and individual circumstances that may influence each finding.

Adapted from A.J. Cruz-Jentoft et al., “Sarcopenia: European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People,” Age and Ageing 39, no. 4 (2010): 412-423. By permission of A.J. Cruz-Jentoft. Licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License 2.0.

Normal BMI and FFM

Refer to reference ranges for normal BMI, FFM, FM, FFMI, and FMI in table 6.2. Inquiries regarding weight history, including recent changes that were unintended or not desired, should be made in addition to body composition to ensure any “normal” values were not achieved at the expense of FFM loss. Serial measures taken early in the course of pulmonary disease or, at least at the beginning of pulmonary rehabilitation, are helpful in accessing body composition changes over time and as the disease progresses.

Obesity and Morbid Obesity

Obesity, defined as a BMI >25 kg/m2, and morbid obesity, >30 kg/m2, are associated with higher mortality and morbidity due to increase in CVD risk. In nonpulmonary, nonsmoking individuals, a BMI between 20-25 kg/m2 had the lowest all-cause mortality risk. But in COPD patients with moderate to severe obstruction, a BMI 2 was associated with higher risk than those whose BMI >25 or even >30 kg/m2. Although weight loss is routinely recommended for all obese individuals, caution should be exercised in recommending weight loss in COPD patients with moderate to severe obstruction. No studies have systematically investigated the effects of weight loss interventions on adiposity, functionality, and systemic inflammatory profile in patients with COPD. Modest reductions in weight can reduce the cardiovascular disease risk through improvements in body fat distribution. A combination of moderate hypocaloric, moderate to high protein diet and aerobic exercise may achieve this goal best because aerobic exercise training improves insulin sensitivity, induces mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle, and induces loss of visceral fat mass. Rapid weight loss is frequently associated with loss of FFM and thus is not recommended in pulmonary individuals.

See table 6.4 for metabolic phenotypes and the related nutritional instructions and considerations during pulmonary rehabilitation.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Sample mental health lesson plan of a skills-based approach

- Sample assessment worksheet for the skill of accessing valid and reliable resources

- Help your students overcome what holds them back from making health-promoting choices

- Example of an off-season microcycle

- Modifying lifts

- Screening for multilevel programs in a team environment