Learn the steps to create an effective in-house research project

This is an excerpt from Monitoring Training and Performance in Athletes by Mike McGuigan.

Conducting In-House Monitoring Projects

Many practitioners cannot afford to wait for published research to confirm the efficacy of a particular monitoring approach. Being able to design and undertake an in-house research project can be a useful skill. An in-house research project is any form of data collection and analysis performed within the sport program to answer a specific question of interest to the practitioner. This could be as simple as determining the reliability of a monitoring tool, or it could be more complicated, such as finding out whether a monitoring tool can determine readiness to train and improve the quality of training sessions.

Without realizing it, practitioners often conduct research on a regular basis when implementing a monitoring system. Of course, the usefulness of this research depends on the quality of the information collected. A retrospective analysis of monitoring data can be particularly useful. This is done by looking back at data collected over a period of time to observe trends and patterns. Sometimes, the decision of which variables to track in athletes becomes clear only after implementing the monitoring system for a period of time. An evidence-based approach can help practitioners make sound decisions about which variables to keep in the system and which to remove.

Both quantitative and qualitative approaches to research can be useful (see chapter 2). Practitioners can use a mixed-methods approach, which includes elements of both. For example, monitoring could include a performance test (quantitative), a wellness questionnaire (quantitative), and a semistructured interview (qualitative). Incorporating several approaches may provide a more holistic view of the monitoring system. Resources for practitioners on how to conduct research projects are available (2, 7, 75).

Asking focused and insightful questions is a critical skill for practitioners, and conducting in-house research projects can be a good way to generate these questions. Having focused questions is a good way to facilitate conversations with other practitioners as well. Practitioners with less experience with data may have a degree of data phobia. Rather than focusing on the numbers themselves, more experienced practitioners can engage in discussions with colleagues about how they are attempting to answer particular problems.

Steps for Completing In-House Research

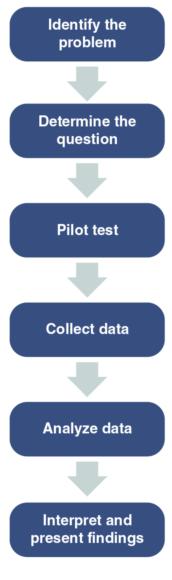

Following are steps for completing in-house research projects:

- Identify the problem.

- Conduct a search of the scientific literature to see what research has been conducted in the area. PubMed and Google Scholar databases are good starting points for searches.

- Talk to other practitioners and researchers in the area to see whether anyone has completed research on this issue. Other practitioners are a popular source of information (73) and may be able to provide suggestions or feedback on your proposed research.

- Consider using social media to reach out to experts for insights on research.

- Clearly define the research question.

- Develop a brief proposal or outline of what the research project will involve. Rewrite it after getting feedback from other practitioners.

- Identify the logistics of the project, including equipment, personnel, the number of athletes, and costs.

- Do some pilot testing of the methods. This helps to identify issues with the methods and can help to troubleshoot problems that may arise during data collection. Things can be very different when monitoring in the field with a group of athletes!

- Complete the data collection.

- Analyze the data using the methods outlined in chapter 2. It is vital to document all methods of data collection, decisions about data analysis methods, and how analyses were conducted.

- Interpret the findings. What do the results mean? This needs to be put in the context of previous literature, have a theoretical basis, and provide at least one practical application.

- Write a summary of the findings. This should include a bottom-line statement of how the results of this research help the program and athletes. Consider alternative methods for reporting the findings. A short video could be an effective way to summarize the findings for those who spend a great deal of time looking at media content in this format. Would infographics that highlight the key findings of the research be a useful way to report the project summary? Because practitioners do not routinely get their information from published research studies (73), alternative methods for disseminating information are worth considering.

- Research always raises new questions, so be prepared to continue this cycle. Figure 7.3 shows a simplified model to follow when undertaking in-house research projects on athlete monitoring.

Research process for athlete monitoring.

Consider a practitioner who wants to assess the effectiveness of a simple test for determining training readiness in a group of athletes. She wonders whether a measure of grip dynamometer strength could be a useful indicator of athlete readiness for resistance training sessions. First, she decides to determine the reliability of the test over the course of a 2-week training block. Grip strength measures are performed before and after each training session. A wellness questionnaire is incorporated to provide a subjective measure of the athletes' responses along with session RPE. The reliability of the measures is determined by calculating the coefficient of variation and intraclass correlation coefficient for the test (see chapter 2). A decrease in grip strength from pretraining to posttraining may indicate the effect of the session on force production. Later, measures of grip strength are taken at certain time periods following training sessions. For example, in addition to the pretraining and immediately posttraining periods, the practitioner measures grip strength 6 hr later and then 24 and 48 hr later. She then compares the time course of these measures with other types of training sessions to see whether grip strength is sensitive to fatigue. What would be more difficult would be to investigate how modification of the training sessions affects athletes' performances both acutely and chronically. However, by monitoring the athletes over the course of a mesocycle, patterns may begin to emerge.

A case study - based approach to in-house research projects can be a useful strategy for practitioners (36). For example, a practitioner may collect data from a variety of monitoring tools for a BMX athlete over the course of a training year and throughout a 4-year cycle leading up to the pinnacle event such as the Olympic Games. In year 1 the practitioner could use an experimental approach that involves collecting a large amount of monitoring data. This would be useful for identifying which monitoring tools are reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Year 1 would also be the time to experiment with interventions to enhance performance, including race day warm-ups and power priming (35). In year 2, the monitoring system could be refined by removing certain tools based on the results from year 1. By the time year 3 comes around, the practitioner would be confident of the monitoring system in place. At this stage only minor tweaks to the system would be required.

Following a research process for determining the validity of equipment can also be useful for practitioners. For example, using different devices to measure the velocity of the bar would allow comparison. Practitioners could attach transducers or encoders to either end of the bar and accelerometry technology to a weight plate. At the same time, the athlete could have some type of wearable device around a wrist or forearm. A similar setup would involve wearing a range of devices for a period of time and comparing the results (40, 66). This way, the practitioner can measure the degree of variability between the devices. Ultimately, making the comparison against a gold standard would be ideal. However, such a standard does not always exist in sport science. For example, a theoretical gold standard for measuring fatigue in athletes would be a maximal-effort sport-specific performance test (78), which is impractical as a daily or weekly monitoring tool.

Learn more about Monitoring Training and Performance in Athletes.

More Excerpts From Monitoring Training and Performance in AthletesSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?