Improve hitting precision

This is an excerpt from Complete Guide to Slowpitch Softball by Rainer Martens,Julie Martens.

Place hitting is more about accuracy than power. As you develop your hitting skills, you'll want to decide whether you want to be a power hitter, a place hitter, or both. In doing so you should know about Fitt's law. This well-established scientific principle of motor behavior is about the speed-accuracy tradeoff. In hitting terms, it means that the faster you swing the bat, the less accurate you'll be. Thus you need to decide whether you want to swing the bat with greater speed or give up some of that speed so that you can hit the ball more accurately. It may be a decision to hit .500 with occasional home runs or hit singles three out of four times to hit .750.

Here are the key things that place hitters do differently compared with power hitters.

- They more often use a conventional grip to maximize bat control.

- They tend to use a more open stance or ready position.

- They are modestly nomadic, making minor location adjustments with their feet in the batter's box as the pitch approaches to position themselves to hit to the location they have targeted.

- The load phase involves less movement. The hands may reach back only a short distance before starting forward in the swing phase.

- The stride is shorter; it's a smooth, soft step that adjusts the position of the batter to the location of the ball to hit it in the direction desired.

- The swing is less powerful (slower speed), and the emphasis is on timing the swing to hit the ball to the desired location.

A less powerful swing doesn't mean a weak swing. Place hitters want to hit the ball sharply too so that fielders have less time to catch the ball. As Fitt's law states, they trade off some speed in the swing to swing more accurately.

Hitting to the Near Field

If you're batting right-handed, the near field is the left side of the field, and if you're batting left-handed, the near field is the right side of the field. Most players learn to hit to the near field when they first learn the game; that is, they learn to pull the ball toward third base if hitting right-handed and toward first base if hitting left-handed. This swing seems to come more naturally, with greater accuracy and more power.

Right-handed batters like to hit the 5-6 hole between the third baseperson and shortstop; left-handed batters may try the 3-4 hole between the first and second basepersons (see figure 2 on page 8 for a review of the holes). If the third baseperson moves away from the foul line into the 5-6 hole, right-handed hitters may choose to hit the ball down the third-base line. Likewise, left-handed hitters may try to hit the ball down the first-base line if the first baseperson moves into the 3-4 hole.

To hit the ball to the near side, you want a pitch on the inside half of the strike zone that is waist to shoulder high at the point of contact. Hitting an outside pitch with accuracy to the near side is difficult, especially if you're trying to hit just inside the foul line. Another pitch to avoid is the low, inside pitch, which if hit will likely go foul or to the third baseperson if you're a right-handed batter and to the first baseperson if you are a left-handed batter. Also avoid deep, inside pitches. Those you'll likely pop up or foul, and they are definitely difficult to hit to a desired location. See Offense→Advanced Hitting→Near- and Opposite-Field Hitting on the DVD to master these skills.

Hitting to the Opposite Field

Hitting to the opposite field (right-handed hitters to right field and left-handed hitters to left field) is a valuable skill not only for place hitters but for power hitters as well. If your opponents discover that you can hit only to the near side, they may shift more fielders to that side of the field. When you hit at least occasionally to the opposite field, defenses must play you straight away.

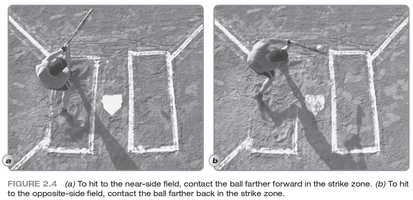

The key difference between hitting to the near-side field and the opposite field is that in the second case you let the ball come farther into the strike zone when hitting it (see figure 2.4a-b). Therefore, to hit the ball between your shoulder and waist, you'll want to stand forward in the batter's box. If you stand back in the box, the ball will more likely be low in the strike zone and more difficult to control.

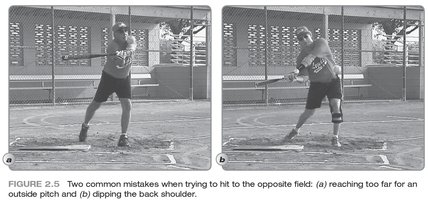

The best pitch to hit to the opposite field is one on the outside half of the strike zone at shoulder to waist height. One common mistake when hitting to the opposite field is trying to hit pitches that are too far outside, resulting in your reaching too much and losing bat control (see figure 2.5a). Reaching could also cause you to step on the plate or strike mat as you're swinging, which is an automatic out. Another common mistake is dipping the back shoulder when positioning yourself to hit (see figure 2.5b). Although you want to rotate inwardly to align your body to hit toward the opposite field, keep the shoulders level. A third common mistake made when hitting to the opposite field (although it can occur when hitting to any field) is pushing the bat in that direction rather than swinging the bat. Pushing the bat refers to batters pushing the bat forward with the back arm (top hand on the bat) rather than pulling forcefully with the front arm (bottom hand on the bat) to get good velocity on the bat head. Consequently, the bat head is farther back when contacting the ball, resulting in little momentum being imparted to the ball. In hitting to the opposite field, you want to maintain good swing mechanics. The adjustments are positioning the body to swing comfortably to the opposite field and delaying the swing slightly. Watch Offense→Advanced Hitting→Near- and Opposite-Field Hitting on the DVD to see these incorrect swings.

Some skilled place hitters are squatters, making only a slight adjustment in the forward stride by stepping in the direction that they intend to hit the ball. They commonly take a position in the batter's box farther away from the plate and then stride toward the opposite field. Most of their adjustment comes in the timing of their swing. They wait longer to make contact, hitting the ball not in front of the body as when they pull the ball, but even with the body. Thus, the defense has more difficulty determining where a squatter will hit the ball.

Other place hitters are nomads. They'll take almost any position in the batter's box, but when the pitch is coming they adjust their position to align themselves to hit to the opposite field. A common approach for nomad place hitters is to take a comfortable stance for hitting to the near-side field but, as the ball is pitched, to step away from the plate with the back foot and to step slightly toward the opposite field with the front foot.

Hitting up the Middle

After the ball is past the pitcher, the holes on either side of the pitcher (the 1-4 and 1-6 holes) are often wide open. And line drives over the pitcher will find the grass between the left-center and right-center fielders. But this kind of hitting calls for precision. If the ball is hit to the pitcher, it's an easy out, and if a runner is on first, it's an easy double play. If the shortstop or second baseperson is playing closer to second base, especially if the fielder knows that you like to hit up the middle, then you should look to hit the 3-4 or 5-6 hole. The best pitches for squatters to hit up the middle are those in the middle of the strike zone from waist to shoulder height. Nomads, on the other hand, will adjust their position in the batter's box to align themselves to hit the pitch wherever it's located, except that they will avoid reaching for outside pitches.

More Excerpts From Complete Guide to Slowpitch SoftballSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?