How do you budget for your organization?

This is an excerpt from Leisure Services Management 2nd Edition With Web Study Guide by Amy R Hurd,Robert J Barcelona,Jo An M Zimmerman,Janet Ready.

Budget Cycle

Developing a budget is a long process with several steps. These steps are called the budget cycle and are prevalent within all sectors of leisure services. Some organizations may modify the process or order of the steps, but the budget cycle remains relatively consistent throughout the profession.

Step 1: Develop a Budget Calendar

A budget calendar is a time line of tasks to be completed, including when budget preparation begins, when the budget is due from each level of administration, when the budget is presented to and approved by a governing body, and when the fiscal year begins. A budget runs on a fiscal year and consists of the 12 months during which a financial cycle runs. A fiscal year does not have to start on January 1 and follow a calendar year. For example, the City of Columbia Parks and Recreation Department in Missouri has a fiscal year of October 1 to September 30, and the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA) has a fiscal year of July 1 to June 30. The budget calendar is based on the start of the fiscal year, and all proposed budgets must be completed, approved, and ready for implementation before the new fiscal year starts.

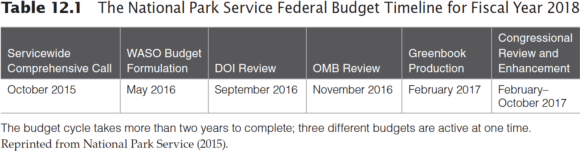

A budget cycle can require working with the budget for more than one fiscal year. For example, in the United States, the National Park Service (NPS) began the creation of the FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 to September 30, 2018) budget in October of FY 2015 with the NPS Servicewide Comprehensive Call. The budget was completed in February 2017 when they submitted the information to Congress. With any luck, they will have an enacted appropriation before the start of the new fiscal year on October 1. The entire budget process in the NPS takes two or more years (table 12.1), with that time frame expanding if a new presidential administration takes office (National Park Service 2017).

Step 2: Develop a Departmental Work Plan

A work plan outlines what programs and services will be offered or what products will be produced. In essence, the work plan forecasts service volume. It also allows for evaluation and opportunities to eliminate unsuccessful programs, services, and products, as well as add new ones. The work plan will drive the budgeting process since the budget should account for the products in the work plan.

Step 3: Develop an Expense Budget

Once the products, services, and programs are outlined in the work plan, it is time to develop the expenses to produce them. A major part of the expense budget is salaries and related employee expenses such as fringe benefits. Salaried employees receive a set annual wage that is broken evenly into the designated pay periods for the agency, and most agencies pay weekly, biweekly, or monthly. This salary, as well as any anticipated raises, should be included. An employee making $40,000 per year and anticipating a 3 percent raise at the beginning of the fiscal year would have $41,200 budgeted for salary.

Hourly employees are different only in that you need to calculate for each position individually. Assume a facility supervisor is working 20 hours per week at $12 per hour. Wages would be calculated as

20 hours per week × 52 weeks a year × $12 per hour = $12,480.

In addition to wages and salaries, all other operating expenditures need to be accounted for, including facility maintenance, equipment, and supplies. Although managers have a tendency to overestimate expenditures in their budgets, this is not good practice. Ideally, a manager will attempt to account for all anticipated expenses fairly accurately knowing that if enrollment is low, they will need to cut spending.

Step 4: Develop a Revenue Budget

Sources of revenues for organizations in the public, nonprofit, and commercial sectors were discussed in chapter 11. It is during this step in the budgeting process that revenue is accounted for, whether it is fees and charges, taxes, or investment income. Many managers are conservative in their revenue projections. It is better to bring in more revenue than projected than to have a shortfall. If the projected revenues do not come in, then the expenses will need to be adjusted in the middle of the fiscal year to account for the change in circumstances.

Step 5: Modify and Finalize the Budget

With the revenues and expenditures in place, it is necessary to analyze whether the budget meets the goals, objectives, and priorities of the organization. This includes ensuring that all subsidy projections are met and that products meant to be subsidized, break even, and turn a profit actually do. This step reviews whether the expenditures are too high or revenues too low. In this step managers are sometimes asked to make budget cuts. They may be told to cut a percentage of money from the budget or given a flat amount to cut, either from reducing expenditures or increasing revenues. If revenues are increased, there should be a justification for doing so. Once revenues are projected, they are expected to actually materialize.

Step 6: Present, Defend, and Seek Approval for the Budget

The finalized budget will go through a review process with the administrative board for public and nonprofit agencies and larger commercial agencies. Small commercial agencies, such as partnerships and sole proprietorships, need only the approval of the owners. Budgets that are presented in front of a board will demonstrate the overall financial picture as well as explain any major increases or decreases in revenues and expenditures. The board usually asks numerous questions seeking justification for some areas. At this point in the process, the board may approve the budget or ask for revisions. Once approved, the budget is set and ready to begin the fiscal year.

Summary of the Budget Cycle

Budget preparation requires involvement from all levels of the organization. Any staff members who are involved in spending money or bringing in revenues should be part of the process. This helps get commitment from staff who must work within the financial parameters set in the budget. In addition, these employees know the inner workings of their programs, services, and products. They will be well versed in what expenditures to expect as well as better able to project revenues than someone higher in the organization who does not work directly with the services, programs, or products.

More Excerpts From Leisure Services Management 2nd Edition With Web Study GuideSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?