Gatekeeping information in sports media

This is an excerpt from Sports, Media, and Society by Kevin Hull.

There is little debate that the sports media plays a major role in how fans consume sports. What teams, games, and stories are shown on television, written about in the newspaper, or shared online are often determined by a very small group of people in leadership roles at each individual media outlet. The concept of gatekeeping demonstrates how the media has that power and how they can use that influence in determining what stories reach the public.

In a hypothetical situation, a local college’s athletic department might send a press release to the media informing them about three events happening on campus tomorrow: a women’s soccer game, a track and field event, and a blood drive sponsored by the men’s tennis team. The newspaper elects to print only a story previewing the women’s soccer game and ignores both the track and field event and the blood drive. Therefore, readers who use that newspaper as their only source of local information might have no idea that either the track and field event or the blood drive is happening. There are multiple events happening at the college, and it was not the readers who decided what was important—the newspaper’s editors decided for them. Situations like this one occur all the time in newsrooms across the world and perfectly demonstrate the concept of gatekeeping.

Definition of Gatekeeping

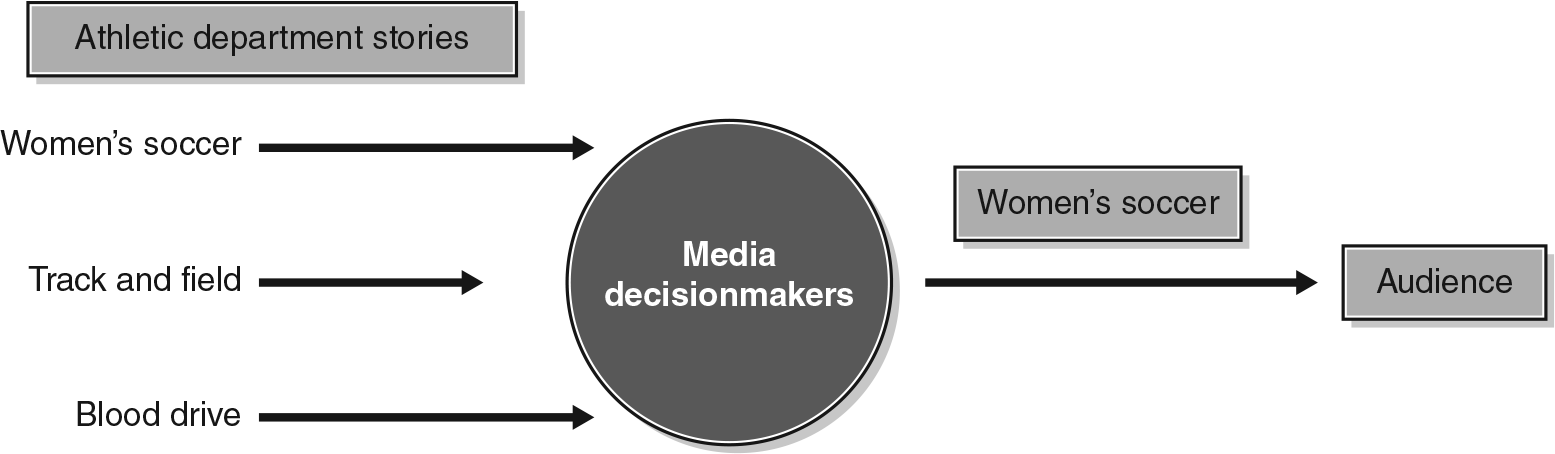

In terms of communication and the sports media, gatekeeping is the process through which information is filtered for the public’s consumption. The process works as follows: There are many different news items that media members are presented with each day. The media then screens these potential stories and decides which ones to present to the public. This process has given journalists the label of “gatekeepers” because they are the ones who decide which news items get past them and reach the audience. News consumers rely on the media to not only examine the numerous stories going on in the world each day and present the most relevant ones to the public but also to frame them in a way in which the most important aspects of those stories are presented. Figure 1.1 demonstrates how gatekeeping would work in a sports department newsroom using our example of the three local college events.

- The athletic department is on the left side of the figure, sending three stories to the media.

- The media, in the middle of the graphic, chooses to allow only one of the stories to pass through the “gate” to the public, while the other stories are rejected and do not reach the audience.

- The audience, on the right side of the image, will hear about only the one story because that is the only one presented to them.

Newspaper editors serve as the gatekeepers because they determine which stories will make it into the newspaper and which will not.

Origin of Gatekeeping

While gatekeeping is known primarily as a media-related theory, that is not how it got its start. One might be surprised to learn that gatekeeping originated as a theory explaining how food ended up on a family’s dinner table. A manuscript written by Kurt Lewin in 1947 is widely recognized as the first formal appearance of gatekeeping in research. In it, he states that not all the stages of meal planning are equal and that certain people, perhaps unknowingly, play an important role in an evening’s dinner. He labeled those people as gatekeepers of the process (Lewin, 1947).

For example, in the grocery store, the manager determines what products that store will carry, making them an early gatekeeper in the consumer’s food-buying process. If the manager decides that the store will carry just chicken and turkey that week, then shoppers at that store will be able to purchase only those items and will be out of luck if they wanted hamburgers. The person doing the shopping is also a gatekeeper. If they buy the chicken instead of the turkey, then that family will be having a chicken dinner. What type of chicken will be decided by another gatekeeper, as the person doing the cooking will decide whether it will be baked, fried, or grilled. However, the home chef might not be cooking anything if the person in charge of putting away the groceries forgets to place the chicken in the refrigerator and accidentally leaves it out to spoil (yet another gatekeeper). As demonstrated here, a family’s fried chicken dinner might seem like a simple meal, but it is actually influenced by multiple gatekeepers along the way before it reaches the table.

Gatekeeping in Communications and the Media

While the concept of gatekeeping was introduced by Lewin, it was a journalism professor who ultimately adapted it to the communications field, in which it is more commonly known. In an article published in 1950, David Manning White examined how a newspaper editor determined which stories appeared in the newspaper and which were left out. For one week, an editor of an unnamed newspaper in the Midwest agreed to keep a record of all the stories that came into the newsroom from the various national and international news services. From that list, the editor would determine which stories would be published. At the end of each day, the editor (cleverly referred to as Mr. Gates in this gatekeeping study) would make a note of why the rejected stories did not make the cut (White, 1950).

Following the full week, White found that 90 percent of the stories that came into the newsroom from these services were rejected by Gates. As for why, White noted that almost every decision was “highly subjective” and “based on the ‘gatekeeper’s’ own set of experiences, attitudes and expectations” (1950, p. 386). Gates rejected articles that he considered propaganda, trivial, or in poor taste. While some stories were rejected based on Gates’s values, others were discarded simply because he had either already selected a similar story or did not have room in the newspaper to include it. Ultimately, White came to the conclusion that an entire community of newspaper readers will only know about stories that the individual editor considered to merit the space, thus demonstrating the incredible influence of these gatekeepers (White, 1950). The study was replicated in 1967 with the same editor and the results were similar, with the author noting that “Mr. Gates still picks the stories he likes and believes his readers want” (Snider, 1967, p. 427). While the type of story that was the most popular choice of Mr. Gates had changed—hard news stories were now more prominent than the human interest stories that had dominated 17 years earlier—the study further demonstrated the influence of the gatekeeper in the newsroom process (Snider, 1967).

What Makes It News?

It is worth examining biases and addressing what aspects of a story make it worthy of being considered for broadcast or publication. To put it more simply: What makes something news? Shoemaker and Vos determined that “a primary characteristic of newsworthy events is whether the event, the people, or the issues are deviant” (2009, p. 25). Therefore, if the event is out of the ordinary, then that makes it more newsworthy. For example, NBA superstar Steph Curry making a three-point basket in the first quarter of a basketball game is not necessarily newsworthy because players (especially Curry) make three-pointers all the time, and a basket in the first quarter is likely long forgotten by the finish. However, since that same basket made Curry the NBA’s all-time leader in three-pointers made, the seemingly insignificant event is suddenly very newsworthy (Jackson, 2021). Setting a record is out of the ordinary, so the basket is now more interesting to reporters and the public.

Other elements that make a story newsworthy include audience interest, proximity, and timeliness (Badii and Ward, 1980; Berkowitz et al., 1996; Shoemaker and Vos, 2009; Stempel, 1962).

- Audience interest stories come about through news organizations surveying their consumers and determining what stories they would like to hear more about.

- Proximity refers to where the story takes place, which can be an important determinant when it comes to local news. For example, the Los Angeles media will likely focus a great deal of attention on the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team, while practically ignoring the New York Yankees.

- When the event takes place (timeliness) is also a key factor when determining the newsworthiness of an event. An evening sports broadcast will have highlights of games that happened that day, while events that happened two weeks ago will not make it into that broadcast.

While sometimes the newsworthiness of a story is obvious, in other cases, individuals make judgments regarding importance of events. The gatekeeping studies from White and Snider both revealed that the editor’s personal opinions and experiences had a significant impact on which stories made the newspaper and which were omitted. In the example that was used in the introduction to this chapter, the blood drive was deemed by the newspaper’s editors to not be a newsworthy event. However, if one of those editors had a family member who had a life-saving procedure thanks to blood donations, they might consider that story something the public needs to hear about. In that case, the editor’s personal history would play a role in the inclusion of the blood drive story. The story is the exact same, but the person judging it is different, and that causes it to suddenly become more newsworthy to a gatekeeper.

More Excerpts From Sports, Media, and SocietySHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW