Organizing Content for Teaching

This is an excerpt from Effective Physical Education Content and Instruction With Web Resource by Phillip Ward,Harry Lehwald.

One of the truisms in teaching is that you must understand what you teach. Your deep understanding of content leads to deeper content learning by students (Ward, 2013; Ward, Ayvazo, & Lehwald, 2014). In addition, the quality of the tasks is critical, because students acquire better knowledge and perform better if you use high-quality tasks. Your capacity to improve student learning is grounded in the professional knowledge that informs PCK. As discussed in chapter 1, PCK is influenced by your knowledge of students, the curriculum, the context in which you teach, the pedagogical strategies you use, and the content you teach.

What does it mean to know content deeply? In the following two examples, much of the teachers' decision-making and many of their instructional behaviors, content representations, and task selections depend on the extent of their SCK. In chapter 2, we argued that SCK is meaningful, relational, and progressive.Itis reflective of deeper content knowledge. When you compare the following two examples, you will see that the second teacher shows a deeper and more explicit knowledge of basketball.

Consider a simple 4v1 keep-away basketball game. The first teacher introduces the game with a demonstration and an explanation. There is an off-the-ball focus of moving away from the defender to receive a pass, and there is a rule that the ball carrier must pass to the open players. The defensive rule is that the ball can be intercepted, but there cannot be any physical contact between players. Students are sent to practice in groups. During the practice, the teacher provides feedback to students. Once the task is completed, the teacher moves the students to the more difficult 3v1 keep-away game.

The second teacher also provides an explanation and demonstration of the 4v1 keep-away game. The focus is the same as in the previous example. However, this teacher begins by requiring the defender to walk and not intercept the ball; this gives students learning the offense time to make decisions relative to the defender (i.e., a passive defense). The teacher prompts students to get open. Next, the teacher asks the defender to move more quickly and indicates that no interceptions are allowed (i.e., an active defense). As the practice progresses, the defender can intercept the ball (i.e., a competitive defense). The teacher pauses game play to emphasize moving deep or wide or to refine the technique. The advantages of this process include the following:

- Small progressive incremental changes allow for student understanding, refinement, and extension.

- Keeping the same instructional format as new concepts are introduced allowing students to build on the original task, which builds competence.

- The creation of high numbers of repetitions that occur as task complexity or difficulty increase, without major changes to the pedagogical conditions of game.

The teacher in the second example uses extension and applying tasks, and the task progression is more incremental and systematic than in the first example. As these two examples show, teaching a skill demands in-depth and detailed knowledge that goes beyond the critical elements and the ability to demonstrate the skill. You must have extensive SCK (Ayvazo & Ward, 2011; Ward, 2009), including knowledge of errors that students could make in performing the task and knowledge of the instructional representations and tasks. The deeper your knowledge, the more choices you will have in adapting instruction for students (Ayvazo & Ward, 2011; Griffey & Housner, 2007; Ward, 2013).

Defining the Scope of Content Knowledge in K-12 Teaching

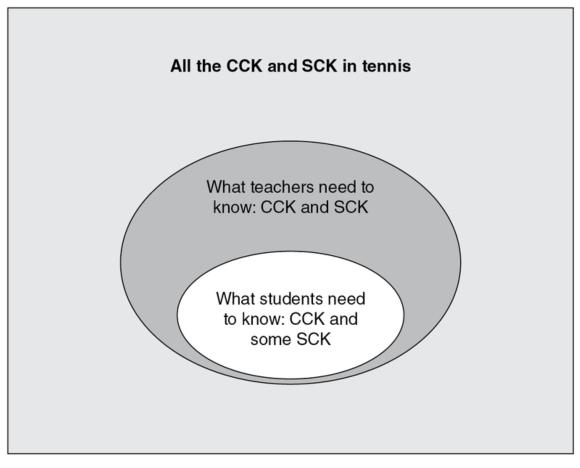

Deep understanding of content does not mean you must know everything about a sport or activity to teach it. Figure 3.1 illustrates the broad scope of knowledge for tennis. The large box represents all that is known about tennis. The smaller circle represents the tennis knowledge students in K-12 settings need. It includes CCK such as rules of the game, safety rules, techniques, and tactics. If you are using an instructional strategy in which one student is teaching another (e.g., peer tutoring), students will also need the SCK required to provide feedback. The larger circle represents what you need to know: the SCK for teaching the CCK in the small circle and the SCK required for adaptations for students with disabilities or more skilled students.

The scope of K-12 content knowledge in tennis.

Principles Behind Our Approach

This book is based on several principles for teaching physical education that are derived from our research and practice over the past 30 years. Here we list these principles and discuss how they influence the contents of the book.

- Teachers are decision makers. You should neither blindly follow a plan nor teach without one; rather, you should adapt instruction from an existing plan that you create or that comes from another source. If you have to create plans for content you know little about, you are likely to experience frustration in your teaching. In addition, student learning will suffer. In this book, we provide models for teaching content. Contexts and students differ, however, so we expect you to adapt these models as needed. It is our firm belief that it is better to operate from a good plan that needs to be adapted than to create a weak plan that is ineffective.

- Experts teach content differently from nonexperts.If you are learning to teach content as a nonexpert, you will probably learn differently than an expert because you have less SCK and less experience teaching this content. The models in this book were not created for experts. They allow teachers who do not know the content well to teach their students successfully and learn from that teachingas they develop increasingly better PCK.

-

In middle school and high school, longer instructional units are preferred over shorter ones because longer instructional units allow more time for skillful performance to be developed, deeper understanding of the game, and for game sense to be developed.Longer instructional units serve students better if they are organized around meaningful, relational, and progressivecontent. There are many arguments for teaching short units in the multiactivity curriculum format. Two common ones are that short units maintain student interest by providing variety and that some students might not like a particular sport but do like another. Students get bored with the typical instruction in most schools (i.e., short units, limited skill development, little development of game sense) because the tasks used in these short units are not meaningful, relational, or progressive.Our goal in this book is to change that to create more engaging units.

Similarly, the argument that students will like one sport over another is misleading. A much better indicator of student enjoyment in physical education is not the sport or activity being taught but rather the way it is taught. In our own teaching experiences, training of preservice teachers, and work with in-service teachers, we have consistently found that content that is meaningful, relational, and progressiveengages students and creates learning and enjoyment.

- In elementary school, instructional units should be related to each other in ways that cumulatively build content. Elementary school teachers have fewer lessons per year than their secondary school counterparts; therefore, we present elementary school instructional units as 5-7 lesson blocks. Our assumption is that many skills transfer across units, such as the ready position (e.g., basketball, volleyball, football), the concept of having fast feet to move into a position to receive the ball (e.g., tennis, volleyball, badminton, softball, baseball), calling for the ball, person-to-person defense, and moving (invasion games). Elementary instruction units should be sequenced to develop complexity and refinement of movements introduced in previous units and to extend and refine movements in later units.

- Small-sided games rather than full-sided games should be taught first in physical education. The question of whether a full-sided game (or a doubles game in a racket sport) should be played is a function of the time it takes to teach students to play the game. In this book, the end goal is to play full-sided games, but to get there you must progress from small-sided games to ensure that students have the skills and the game sense to be successful. The modified games we provide represent the main features of full-sided games. If longer instructional units are used, students in middle school and high school might be able to progress toward full-sided games.

- Skillful performance in sports is a function of technique and game sense. We use the term technique to describe the critical elements of the performance of a movement such as how to hold a bat in softball, assume the starting position, swing, and follow through. The term game sense refers to"the ability to use an understanding of the rules, tactics, strategy and of oneself (and of one's teammates) to overcome the problems posed by the sport or by one's opponents" (Launder & Piltz, 2013, p. 16). Game sense is represented by what players do in the game to demonstrate their understanding, such as reading the play and making decisions. When players apply the rules in the game, they are demonstrating game sense. Technique development and game sense are highly interdependent. This interdependence has been described by Launder and Piltz (2013, p. 59) as "what is tactically desirable must be technically possible." In short, if the goal is to play the game, then technique and games sense must be developed synchronously.

Develop Working Technique

In her article "It's OK to Be a Beginner," Rink (2004) observed that being good or not good at motor skills is not a permanent condition for children and youth. That is why we have teachers. The variety of abilities found in physical education classes means that at any given time, students are at different places in their learning of motor skills, knowledge, and understanding and use of affective skills. Rink's point is that your goal is to move all students forward, and it is important for students to understand that they will get better with practice. Given that students arrive in class at different places in their learning, Launder and Piltz (2013) have suggested the need to develop a working technique. Using a working technique, a student moves from A to B, in which A represents the student's current level and B is where you would like the student to be at the end of instruction. The student should travel the most effective and efficient road between these two points. In this example, the road represents technique. Even beginners should have a working technique that places them on the road to improved learning.

In the Working Technique in Volleyball sidebar, Dr. Dena Deglau, a professor of physical education and an expert volleyball teacher, describes the development of a working technique.

Dr. Deglau clearly has deep content knowledge of volleyball. Her example highlights the developmental nature of working technique. Our point is that teachers must determine what are the essential elements of a working technique that they want to develop as they teach their students. A teacher's understanding of a working technique and their expectations for students will likely change over time as they reflect and tinker with their instruction.

Working Technique in Volleyball: Example of Development

Beginners

To begin to understand how the game is played, young children need to learn how angles affect where the ball will go. They will have some experience with this from the use of paddles and racquets in other activities. However, the force production demands are different in volleyball than in racquet sports. In racquet sports students learn that more force is generated by swinging the paddle faster. In volleyball, students must not think of their arms as having this function. In volleyball, students must learn that force production is generated differently.

Students will often exclusively focus on the forearm pass as beginners, which is the most used skill in the game.

- Students will move and receive the ball in the center of their body at thigh height (young children can move and let the ball bounce between their legs and then move and catch).

- Student should learn to change the degree of bend at the waist and recognize how this affects the trajectory of the ball regardless of what they do with their arms. Students learn to place their arms forward and locked as they try to forearm pass in ready position, then straightening the torso a little. They will learn that this is required if you are bumping repeatedly to yourself and that in a game, the closer you are to the net, the straighter your torso should be.

- Students should learn that force production occurs from the legs and not from swinging their arms.

Beyond the Initial Performance of the Forearm Pass

To approximate the game, students at this level would build from the forearm pass to understand the spatial relationship of the ball relative to body position and target. Here students must understand the three performance characteristics that afford or constrain one's ability to play a modified game

- Move and receive a high ball in front of the forehead. Most students cannot position their bodies appropriately in relation to the ball, and thus the set or volley looks like a throw or hit off the hands. They contact the ball behind or on top of the head, and this constrains the ability to correctly volley the ball.

- Move and volley the ball to someone in front of you. This is truly a volley. Students receive the ball in front of them, and then volley it to someone in front of them. This would lead to continuous passing back and forth with a partner.

- Move and set a ball in a different direction. For example, if a free ball comes over the net to team A, the back-row person would volley or bump the ball to the setter. The setter is standing sideways at the net and must move behind and around the ball to set it to the hitter. Students can't execute a set in the game because they can't move sideways from the net and position themselves correctly to pass to a hitter. If the setter faces the teammates while waiting for the pass to the front row instead of standing sideways, the task of moving around the ball to face the hitter is even more difficult.

I intentionally make a distinction between volleying and setting. The difference is the orientation of the body to the ball and the target. Volleying occurs when the ball is coming directly at you and you are passing directly back (continuous passing back and forth). Setting occurs when the ball is coming at you from the side and you must set in front of you (setter to hitter).

Thisunderstanding extends to the hitter who will set the ball over the net instead of hitting or tipping it over in grade 6. The ball is coming from the setter, so the person getting the ball over the net must see the ball coming from the side, move around and behind the pass, and then set it forward over the net.

More Advanced Performance of the Forearm Pass

At this level of performance students need to understand the spatial relationship of the ball with the body, the target, and the net (height above and distance from). This allows the hitter to learn how to do more than set or bump the ball over the net. Students will also need to develop the ability to execute the cycle of the game. Here students must learn and understand the three new performance characteristics that afford or constrain one's ability to play in a game.

- Students who understand how to tip a ball relative to the height and distance from the net can jump and catch a ball above the forehead. This develops the timing of the jump for the spike. Students need to understand how their movement must be adapted to account for differing sets. Often they are forced to bump the ball over instead of setting or tipping because their movement is too slow relative to the set.

- To learn to play the game, students must inherently learn how to move from the passing position to hitting, setting, or defensive positions. These patterns need to be built into tasks.

Implement a Sport Education Curriculum

We used the term meaningful in chapter 2 to refer to instruction that is connected to students' past learning experiences and knowledge and the real-world context of the activity. The focus is on developing skillfulness in the students so that they can perform modified versions of the activity that are consistent with how it is performed in the real world while valuing and enjoying the movement experience. Though there are many ways to achieve this, we think one of the best is the use of the sport education curriculum and instructional model (Siedentop, Hastie, & van der Mars, 2011) in combination with content knowledge. You do not have to use the sport education model with the content in this book, but we recommend it.

Sport education has several pedagogical features that allow you to present content in meaningful ways. In this section, we discuss the key features of sport education. A more complete description of sport education can be found in the Complete Guide to Sport Education by Siedentop, Hastie, and van der Mars (2011).

Seasons

Creating seasons provide a similar structure to that used in sports. There is often a practice season followed by a competition season. In our secondary block plans, we provide 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-day plans. Three-quarters of the unit is typically the practice season, and simple games take place each day. The tournament season lasts 2 to 5 days, and the primary focus is competition. Several games are played each day against different opponents.

Team Affiliation

Sport education assumes that you will make every effort to create mixed-ability teams, because this is the most equitable strategy to ensure that students perceive the game play as fair. Affiliation is created in sport education by placing students in the same teams for the duration of a unit and providing a team identity (e.g., team colors, team name, team cheer, home field or court, team mascot). We recommend that teams be named after college or professional sports teams, depending on the sport. Teams can adopt the colors, icons, or cheers of these teams (e.g., "Go Bucks" is an Ohio State cheer).

Lesson Management

A central feature of sport education is that students share in the management of and responsibility for the lesson because each person has a role. There are many possible roles to be filled. With groups of four (either one team of four students or two teams of two for racquet sports), we have used the roles of captain, trainer, equipment manager, and statistician. Descriptions of these roles can be found in the Common Team Roles in Sport Education sidebar. To introduce these roles, you must explain the tasks that a student will do in each role. We typically introduce the roles at the beginning of the unit and leave students in the same roles for the duration. If we have additional students, we create new roles or co-roles.

Common Team Roles in Sport Education

Team Roster

- Captain

- Captain's assistant

- Equipment manager

- Trainer

- Statistician

Roles

Captain

- Start the game (rock, paper, scissors).

- Act as a referee during game play.

- Call wall (a defensive strategy) for the team.

- Keep the team on task.

- Line up the team to shake hands at the end of the game.

Captain's assistant

- Hand out and turn in team quizzes.

- Hand out and collect pedometers.

Equipment manager

- Keep equipment neat and organized.

- Set up equipment when needed.

- Return equipment to the proper location at the end of class.

Trainer

- Lead the warm-up activity.

- Keep the team on task during the warm-up.

- Encourage teammates to accumulate pedometer steps.

Statistician

- Record fair play points.

- Record pedometer steps.

- Record game points.

Records

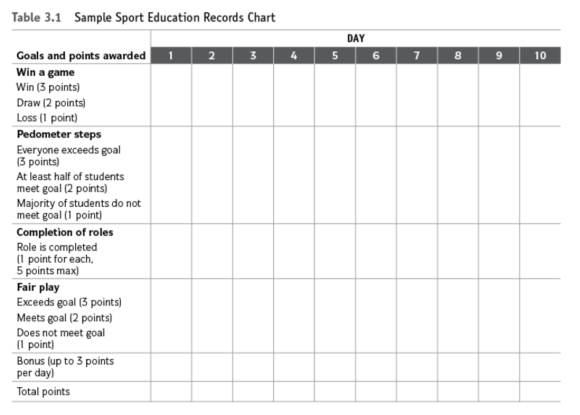

Records are kept in sport education. We find that the easiest method is to use a team chart (see table 3.1). On this chart we record wins and losses, pedometer steps (a goal is set each day),completion of daily roles, fair play (see the web resource for a printable fair play form), and bonus points for good behavior (e.g., extra effort in performance, starting quickly after warm-up, the entire team starting the warm-up on time, excellence performance).

Fair play guidelines are as follows:

- Be respectful to yourself, other players, officials, and equipment.

- Know and play by the rules.

- Practice self-control prior to, during, and after class.

- Give full effort, and appreciate others' efforts.

- Smile and have fun.

You assign the points. The statistician is responsible for recording the points each day at the end of class. These points can be accrued during the unit and totaled at the end to identify the teams with best win-loss and fair play records and to allow the teams to play for a championship on the final day of the unit (see next section).

Culminating Event

The last day of the unit is reserved for a culminating event. Such an event can take many forms, but we typically have pairs of teams (ranked by win-loss records) play championship games. Then we have an awards ceremony in which the teams march onto the field and line up. We award teams and individuals based on specific categories. Some examples of these awards are provided in the web resource. You can print and use these awards or adapt them to suit your needs.

Pedagogical Features in Knowledge Packets

Our goal is to provide you with an organizational framework that will allow you to not only understand the content but also to make instructional decisions about the content as you select and use it in your teaching practice. Central to this goal is understanding why we have not provided specific lesson plans in this book (other than our examples of lesson plan organization and block plans). One of the great contributions of the late Alan Launder (Launder & Piltz, 2013) was his insistence that physical education teachers need to observe student performance relative to the assigned task and then introduce the next task that will further develop student performance. Although you need a plan to guide you, the overall goal you are trying to accomplish (e.g., skillfully playing a 4v4 game) and knowing the steps (i.e., the instructional tasks and the sequencing of tasks toward the major goals) are a critical element of teaching. You must observe the performances and make the best decision on the basis of your knowledge and what you see as the performance needs of your students. This book provides you with the knowledge about the big picture in terms of the content to be taught. Knowing all of the content to be taught allows the teacher to make informed instructional decisions about which content to use in particular learning contexts. We organized chapters 4 through 12 as knowledge packets (Ward et al., 2014) that present what (i.e., the big picture) you need to know to teach the content (as shown in figure 3.1 earlier in the chapter).

Each chapter begins with a description of the pedagogical approachwe recommend for teaching the content. Subsections discuss task modifications to address the needs of students with disabilities, organization of students for instruction, and space and equipment needs.

Next, we provide content maps. These provide an overview of the instructional tasks and the relationship among them and a broad recommendation about when content might be introduced in the K-12 curriculum. With this information, you can decide where your students are in their performances and then select instructional tasks to advance them. There is a combined content map that illustrates the flow of the tasks used to develop sport-specific techniques and tactics starting with beginners and ending with advanced players (in school settings). The combined content maps for chapters 6 through 12 are divided into three levels, and each level has its own separate content map that includes the application games (outline of box is dashed) used to refine the techniques and tactics in that level (outline of box is solid).

Then we provide our recommendations for lesson structure based on the content. An important feature of our lesson structure is a belief, common to many games pedagogies, thatstudents should play games that teach them to use what they have learned in past lessons at the start of the current lesson and to use what they have learned in the current lesson at the end of the lessons. We call these application games.Many of our instructional tasks are presented as games (e.g., overload games in invasion sports, target games in volleyball and badminton) to emphasize a particular outcome. However, application games allow new techniques and game sense elements to be added to previous outcomes to strengthen student performance. Application games are important pedagogical tools that allow you to determine the performance of the students; as such, they can drive the selection of instructional tasks to meet the needs of students. The lesson plan organization examples include sample warm-up activities that have been used for elementary and secondary classes.

In chapters 4 and 5 we provide sample 5- and 7-day block plans, and in chapters 6 through 12 we provide 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-day block plans for each content area. These block plans are organized according to the lesson format we just described and provide examples of the content that could be used depending on the duration of the unit and the experiences and abilities of the students.

Next, we identify key grade-level outcomes for K-12 physical education and match them with instructional tasks in the content map. This allows you to choose which tasks you will use to meet specific standards.

The remainder of each chapter is devoted to presenting the instructional tasks. Each instructional task is organized using the following headings:

- Purpose

- Description

- Equipment

- Critical elements and cues

- Common errors, causes, and corrections

Learn more about Effective Physical Education Content and Instruction With Web Resource.

More Excerpts From Effective Physical Education Content and Instruction With Web ResourceSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?