Learn about intersectionality in health education

This is an excerpt from Intersectionality in Health Education by Cara D Grant,Troy E Boddy.

Preface

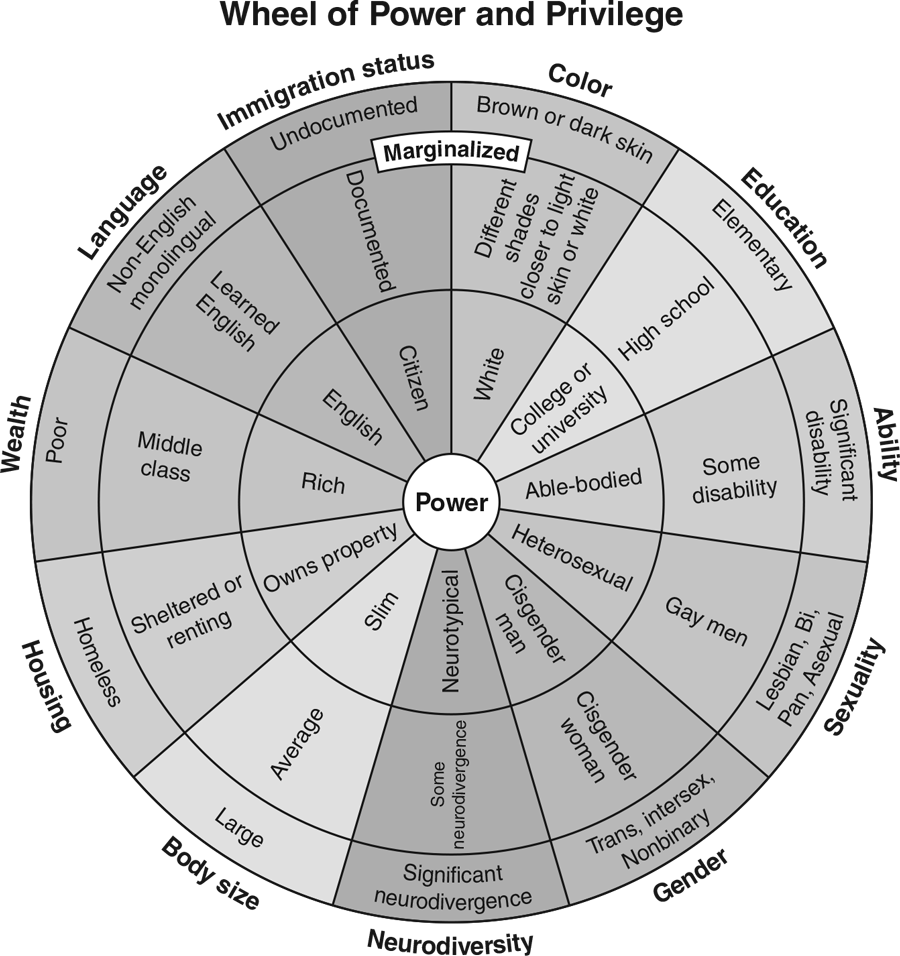

The concept of intersectionality is derived from the 1991 work of Kimberlé Crenshaw (2017), where she unpacked being Black and a woman in terms of racial bias or discrimination and gender bias. Applying the work of looking at the intersections or intersectionality of many marginalized groups in health education can help educators identify and build classrooms where all students see themselves and a dominant narrative does not erase groups of people. Intersectionality can be expanded to any combination of marginalized groups of people—for example, being Latina (Hispanic and female); being an immigrant, dark skinned, and queer; or being poor (low socioeconomic status), homeless, and having a mental health disorder.

This book discusses marginalized groups who identify as “Black and …” Some descriptions of intersectional considerations include the following, elaborating on Crenshaw (2017) and Duckworth (2020):

- Largeness in body size as opposed to the slim European ideal put forward in advertising

- Vulnerability to mental health needs

- Neurodiversity

- Sexuality (bisexual, lesbian, pansexual, asexual, gay)

- Ability (some impairment or significant disability)

- Formal education (having little more than high school or elementary education)

- Skin color (dark skinned, different shades of brown or black)

- Citizenship (undocumented or documented immigrant)

- Gender (transgender, intersex, nonbinary, cisgender woman)

- Language (non-English monolingual speaker, learned English)

- Wealth (poor, middle class)

- Housing (homeless, sheltered, renting)

Combining multiple facets of who students are may or may not put them heavily in marginalized categories and groups of people. Historically, marginalized groups are directly limited in access to health care based on social determinants of health. Those who enjoy the most privilege (slim, good mental health, neurotypical, heterosexual, able-bodied, postsecondary educated, white, citizen, cisgender, male, English as first language, rich, and with property ownership) continue to have the most access and are centered closest to access and power (Duckworth 2020).

The goal of this book is to prompt readers to begin having conversations and reflecting on where we are in health education. Start by looking at yourself and identifying where you are in the Wheel of Power and Privilege (see figure P.1). Then take a look at your school district or school data to see where the students you teach are. Overlap the points to see what commonalities you have and what differences are elevated.

Courtesy of Canadian Council for Refugees.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?