Fundamental distinctions and definitions in motor learning

This is an excerpt from Motor Control and Learning 6th Edition With Web Resource by Richard A. Schmidt,Timothy D. Lee,Carolee Winstein,Gabriele Wulf,Howard N. Zelaznik.

You may have the impression that motor learning and motor memory are two different aspects of the same problem, one having to do with gains in skill, the other with maintenance of skill. This is because psychologists and others tend to use the metaphor of memory as a place where information is stored, such as a computer hard drive or a library. Statements like "I have a good memory for names and dates," or "The person placed the phone number in long-term memory," are representative of this use of the term. The implication is that some set of processes has led to the acquisition of the materials, and now some other set of processes is responsible for keeping them "in" memory.

Memory

A common meaning of the term motor memory is "the persistence of the acquired capability for performance." In this sense, habit and memory are conceptually similar. Remember, the usual test for learning of a task concerns how well the individual can perform the skill on a retention or transfer test. That is, a skill has been learned if and only if it can be retained "relatively permanently" (see chapter 9). If you can still perform a skill after not having practiced it for a year (or even for a day or just a few minutes), then you have a memory of the skill. In this sense, memory is the capability for performance, not a location where that capability is stored. Depending on one's theoretical orientation about motor learning, memory could be a motor program, a reference of correctness, a schema, or an intrinsic coordination pattern (Amazeen, 2002). From this viewpoint, as you can see, learning and memory are just "different sides of the same behavioral coin," as Adams (1976a, p. 223) put it (see also Adams, 1967).

Chapter 9 introduced the motor behavior - memory framework that connects the temporal evolution of motor memory processes and the phases of motor learning (Kantak & Winstein, 2012). Memory researchers describe the information processes as encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. Because learning and memory are just different sides of the same behavioral coin, we can map motor learning processes onto memory processes using this framework. Thus, acquisition or practice corresponds to the encoding processes of a motor memory, and the end-of-practice or immediate retention phase of motor learning corresponds to consolidation processes where the memory is somewhat more fragile, and finally, the delayed retention or transfer phase that represents retrieval processes are referred to as recall. We refer back to these memory processes throughout this chapter as they relate to retention and transfer.

Forgetting

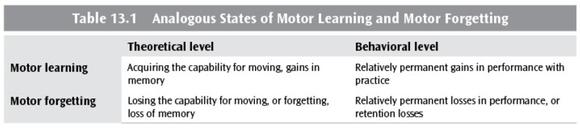

Another term used in this context is forgetting. The term is used to indicate the opposite of learning, in that learning refers to the acquisition of the capability for movement whereas forgetting refers to the loss of such capability. It is likely that the processes and principles having to do with gains and losses in the capability for moving will be different, but the terms refer to the different directions of the change in this capability. "Forgetting" is a term that has to do with theoretical constructs, just as "learning" does. Memory is a construct, and forgetting is the loss of memory; so forgetting is a concept at a theoretical, rather than a behavioral, level of thinking.

As shown in table 13.1, the analogy to the study of learning is a close one. At the theoretical level, learning is a gain in the capability for skilled action, while forgetting is the loss of same. On the behavioral level, learning is evidenced by relatively permanent gains in performance, while forgetting is evidenced by relatively permanent losses in performance, or losses in retention. So, if you understand what measures of behavior suggest about learning, then you also understand the same about forgetting. Remember that we cannot measure forgetting directly; like learning, it must be inferred from performance. As such, an inability to retrieve a specific memory may only reflect a problem with the retrieval mechanism and not the memory itself. A good example of this phenomenon is behavior after head trauma when a loss of memory is evidenced by forgetting. With time, however, the person is usually able to retrieve the information and thereby demonstrate that memory was intact all along but the retrieval processes were temporarily impaired (Coste et al., 2011).

Retention and Transfer

Retention refers to the persistence or lack of persistence of the performance, and is considered at the behavioral level rather than at the theoretical level (table 13.1). It might or might not tell us whether memory has been lost. The test on which decisions about retention are based is called the retention test, performed at a period of time after practice trials have ended (following the retention interval). If performance on the retention test is as proficient as it was immediately after the end of the practice session (or acquisition phase), then we might be inclined to say that no memory loss (no forgetting) has occurred. If performance on the retention test is poor, then we may decide that a memory loss has occurred. However, because the test for memory (the retention test) is a test of performance, it is subject to all the variations that cause performances to change in temporary ways - just as in the study of learning. Thus, it could be that performance is poor on the retention test for some temporary reason (fatigue, anxiety) or a problem with the retrieval processes mentioned earlier, and so one could falsely conclude that a memory loss has occurred. (At this point it might be helpful to review the learning - performance distinction presented in chapter 9.)

For all practical purposes, a retention test and a transfer test are very similar. In both cases, the interest is in the persistence of the acquired capability for performance (habit). The two types of tests differ only in that the transfer test has individuals (all or some) switching to different tasks or conditions, whereas the retention test usually involves retesting people on the same task or conditions.

Learn more about Motor Control and Learning, Sixth Edition With Web Resource.

More Excerpts From Motor Control and Learning 6th Edition With Web ResourceSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?