Exercise progressions to take your workout to the next level

This is an excerpt from Plyometric Anatomy eBook by Derek Hansen & Steve Kennelly.

Using the correct exercises at the appropriate time in a training program is key to ensuring enough stimulation for a positive adaptation but without creating excessive stress that can lead to injury. For a program that is ultimately preparing for explosive plyometric jumps, take care to introduce exercises that are not too complex or stressful. At the same time, the initial steps of a plyometric program should be stressful enough to lead to a progression to the next level.

One of the most basic exercises is a jump onto a box or platform to train concentric jumping abilities. Jumping onto a box provides the benefit of training explosive extension at the hip, knee, and ankle (also known as triple extension) without the impact of a stressful landing. Ideally, the box height will be just below the height of the apex of the jump so you are able to complete the jump safely but also land just after you begin to descend.

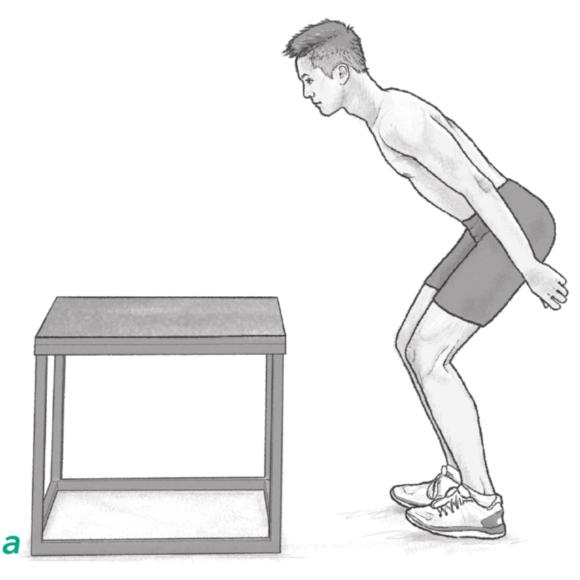

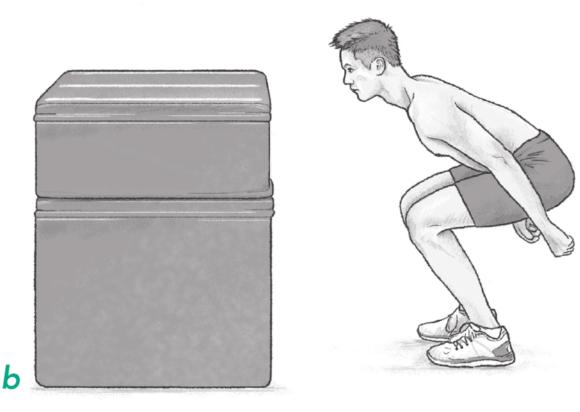

Initially, you can jump onto a box or platform at a static start position from various squat depths as illustrated in figure 2.1. You can perform quicker jumps to a low- or moderate-height box with a small degree of knee flexion at the start. You can do more powerful jumps to a higher box from a deeper knee bend. In both cases, the emphasis is on a quick concentric motion that does not require you to gather for the movement.

Static start positions for jumps onto a box: (a) little knee flexion; (b) deeper knee bend.

Once you have demonstrated competence in the static-start box jump, move to countermovement jumps. Initiating a strong downward countermovement gives you access to the benefits of the stretch-shortening cycle to produce greater force for the upward jump. The landing on top of the box is the same as for a static-start jump - land softly after the apex of the jump.

Other jumping methods that can be used early in a training program are basic jumps in place in a swimming pool. The water provides resistance for the concentric portion of a jump and a significant amount of unloading for the landing phase due to buoyancy in the water. Chest-deep water is a perfect environment for introducing jumps in place that develop strength and power. Perform basic squat jumps initially, one repetition at a time, to work on posture, jumping technique, and landing strategy. As you progress over several sessions, add rebounding jumps that introduce low to moderate loading of plyometric qualities. The pool environment allows progress into jumps over distance as well; the water provides external resistance to movement while challenging balance on landings. The forgiving nature of the pool environment demonstrates how it can be useful for incorporating and reintroducing plyometrics in the context of rehabilitation and return-to-competition training.

As strength and power improve through concentric jumps and moderate-load landings, exercises gradually move into more demanding landing scenarios. Jumps in place are a good means of continuing to develop concentric power while incorporating technical work on landing mechanics. While many athletes know how to jump and take off, other athletes may require more work on the technical aspects of landing safely. A simple squat jump in place can be used to train all aspects of the jumping motion. On landing, learn to properly absorb the forces of a landing through multiple joints and muscle groups, decelerating the body appropriately. As you demonstrate good landing mechanics, progress to multiple jumps in place, such as multiple squat jumps. Initially, these jumps do not need to be high; simply focus on absorbing force and reversing the body's direction from descending to ascending. These low-amplitude jumps not only provide appropriate training stress but also give you time to develop proper technique and timing with lower intensity. As training progresses, jumps in place can become more aggressive, with greater height and shorter ground contact time.

Gradually, low-amplitude jumps in place progress to jumps over distance, adding a horizontal component to the movement. Horizontal travel adds complexity to the movement and stresses the body in a new way to combat the body's gradual adaptation. As with jumps in place, you can introduce lower-amplitude jumps over distance initially, with greater heights and distances for individual jumps improving from week to week. You can perform a low-height pogo jump in place over a 5- to 10-meter distance with low, short jumps of no more than 30 centimeters per jump in the initial phases of a horizontal progression. These jumps can gradually increase to 50-centimeter lengths and also increase in height as you adapt to both the horizontal and vertical forces.

Another variable managed through the implementation of plyometric progressions is the use of two legs versus one leg for jumping movements. It is generally accepted that double-leg movements are relatively less stressful and less complex than single-leg movements. Jumps with a single leg can provide a greater proprioceptive challenge, necessitating stable landings and additional hip and knee control. Single-leg jumps can be used to simulate single-leg takeoffs in jumping sports as well as prepare the body for cutting movements used in various sports and agility training. Thus introduce double-leg jumps initially in a training program and then integrate single-leg movements gradually as strength, stability, and technical competence increase. In many ways, the transition from double-leg to single-leg exercises can be seen as a trend from general work to more specific work in a training program.

As you progress to maximal-effort jumps over distance, extend the distances to provide additional load. Initially, jumps may be over 10 meters, with five to seven jumps constituting a single set. Sets may be expanded to 20 to 30 meters and include improvements in both vertical height and horizontal velocity. It is important to progress carefully when adding both height and distance to your jumps over multiple repetitions and sets because the overall loading stresses can rapidly accumulate to a point where fatigue is excessive and the risk of injury significantly increases.

Add vertical barriers in the form of hurdles to provide tangible goals of height for multiple jumps. Select hurdle heights that encourage you to jump maximally, but avoid excessive heights that increase the risk of tripping and falling. Athletes often enjoy the feeling of jumping over a barrier as part of a plyometric routine to give them a sense of achievement and an indication of jump height. Lower hurdles can be advantageous for large groups of athletes with varying jumping abilities. Less explosive athletes can still jump over lower hurdles safely, while more explosive athletes can simply jump higher over the lower hurdles and still accomplish an effective workout session.

Depth jumps specifically target the stretch-shortening cycle with the use of precise box heights. In a depth jump, you step off a low- to moderate-height box, descend to the floor, then perform a maximal reactive jump back into the air.The exercise can be set up so that you jump onto a higher box or over a relatively high hurdle after jumping back into the air. Each repetition is carefully set up to ensure that the drop is consistently executed and a relatively short ground-contact time is achieved on the reactive jump. A depth-jump session can be a stressful workout because of the magnitude of load experienced at ground contact, particularly if a taller box is used. In most cases, athletes perform two-foot jumps because of the impact stress. You can perform single-leg depth jumps, but drop heights must be relatively low so you maintain short ground-contact time and minimize the risk of injury. In a plyometric jump progression, you may use depth jumps in the latter stages of a preparatory phase after you have accumulated a significant amount of strength through other types of jumps and plyometric exercises as well as strength and power contributions from conventional weight training.

As a further step in the progression, you can perform combinations of hurdle and box jumps in series to create a challenging but enjoyable experience. Drop off a box and then jump over hurdles or onto other boxes in an organized obstacle course of vertical barriers and platforms. It is important to have an appropriate combination of heights of boxes and hurdles to ensure that the equipment elicits maximal output on every jump while not overloading or exhausting you. As with any plyometric exercise routine, the intent is not to burden you with fatigue but to elicit the maximal stretch response from connective tissues. High-quality plyometric work results in positive adaptations for power and speed that enhance overall performance in your sport.

Figure 2.2 illustrates a conceptual approach to progressing into and through plyometric activities over the course of a training program. Early in the program, the intent is to introduce less stressful, less complex movements that provide foundational strength and coordination for subsequent exercises in the progression. The rate at which you can move through the progression depends on age, ability, experience, body weight, and existing strength level. For example, an athlete younger than 10 years may use only the first few stages of the plyometric progression spread over his entire training season. Simple box jumps and jumps in place provide adequate stimulus for improvements in strength and power while not risking injury. However, an older and more advanced athlete may move quickly through the entire progression, using different exercise types at the same time if she has experience with a comprehensive plyometric program over several training seasons. A larger, heavier athlete may never progress up to hurdle jumps or depth jumps because of the risk of injury. Hence, a 350-pound American football lineman requires a significantly different plyometric progression than a 175-pound basketball point guard of the same age and level of development. General guidelines for implementing a safe and effective plyometric progression are useful when individualizing a training program.

Sample plyometric progression throughout a training season.

While you will carry out most of these jumps in a linear fashion, you can introduce additional complexity by including rotational movements and lateral jumps. For box jumps with a static start or a countermovement, jump up and land with a 90-degree turn in either direction. You can also add rotational movements to jumps in place or over distance. Consider incorporation of rotational movements and lateral jumps advanced techniques that improve overall coordination and landing ability in a multidirectional fashion.

Learn more about Plyometric Anatomy.

More Excerpts From Plyometric Anatomy eBookSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?