Community PA programs can take advantage of missed opportunities

This is an excerpt from Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents by Dianne S Ward,Ruth P Saunders,Russell R Pate.

Children and adolescents get most of their physical activity after school. They participate in sport programs, take dance or karate lessons, or just spend time riding bikes and playing with friends. On weekends and in the summers, young people are free to pursue their interests most of the day. Although many youth participate in community sports and recreation, for others, these are times of missed opportunities for physical activity (Sturm, 2005). For inactive young people, the hours between school and bedtime are time to watch TV or videos, play video games, use the computer, or talk on the telephone. Although the nonschool period has much potential for physical activity interventions, few formal interventions have been developed to address youth who are inactive outside of the school setting. As alarm grows over the increased levels of obesity in our society and the relationship of physical inactivity to this problem, employing numerous community settings and these rich time opportunities for intervention might be very useful.

Making the Most of the Community Setting

In intervention development, a community is any group of individuals connected by some aspect of their lives, including geography (neighborhood or housing development), social interaction (religious affiliation or club membership), or shared identity (ethnic group) (Pate et al., 2000). Community physical activity settings might include the following:

- Schools (during and after school)

- Religious institutions (e.g., church youth groups)

- Social and fraternal organizations (e.g., Boy Scouts)

- Neighborhood groups (e.g., housing developments or community clubhouses)

- Community-based organizations (e.g., Boys & Girls Clubs or YMCA)

- Streets, parks, and greenways (around a specific neighborhood)

- Clinical settings (e.g., physician's office or health department clinic)

- Media (e.g., TV, magazines, or billboards)

Many community intervention programs have been developed in appropriate settings to target specific communities, such as Latino youth in a soccer league or African American girls living in public housing.

Unlike interventions that take place at school, community interventions take place in programs that children and adolescents are not required to attend. Youth can choose to attend or not attend, can come late and leave early, or can drop out entirely. Young people might have more motivation for physical activity in a community-based program than in school because they chose to attend it. In addition, community settings might be able to provide a greater variety of physical activity opportunities compared to those available at school because they are not constrained by geography. Other beneficial aspects of community-based physical activity programs include opportunities to make physical activity the social norm, or the "thing to do." Included in community programs are important adults like coaches, family members, or church leaders. Community programs or initiatives might also institute permanent changes in the physical environment, such as the development of a playground or a walking trail or the development of policies that provide greater access to physical activity programs or spaces (e.g., opening school gyms during the evening for community use).

Using Behavior Theory in Community Interventions

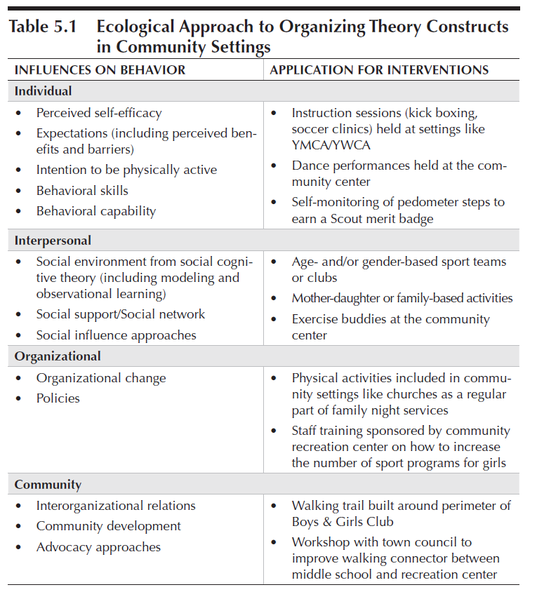

Community-based, youth-oriented physical activity programs should focus not only on the individual child, but also on other components of the environment that affect young people's physical activity. These include the social setting, the physical environment, policies and regulations, and transportation. An effective community physical activity intervention might also include such components as promotions, marketing, and complementary family programs. Using the ecological model allows program planners to simultaneously focus on multiple levels of influence around a child, increasing an intervention program's ability to address the various factors that appear to affect physical activity behavior. Table 5.1 illustrates how the ecological model can be applied to interventions that occur in the community.

Organizing Community Interventions

Community physical activity interventions can be organized around a single purpose, such as the promotion of physical activity in youth or decreased inactivity through encouraging youth to watch less television. Some community interventions are more complex and focus on such multiple outcomes as diet and physical activity behavior. Programs that attempt to intervene directly on a health outcome, such as decreasing or preventing overweight in children, are the most complex and intensive. To make a measurable impact, great effort, resources, and often multiple years of intervention may be required. This chapter includes these more comprehensive, and often more costly, interventions because the information might be useful for the development of new and less elaborate physical activity interventions.

Two approaches can be taken to design community physical activity interventions for children or adolescents. One approach is for interested organizations such as a university or government agency to organize, sponsor, and administer a program. Such an effort would be considered a physical activity program located in the community. The other approach is for interested organizations to partner and conduct the intervention collaboratively. This approach would be considered a physical activity program conducted with the community. Advantages of the first approach include expediency and control, whereas the second approach gets high marks for local identity and sustainability. Development of a program located in the community consists of finding an appropriate location, collecting local information, designing a community-specific program, and implementing the program for a specified period of time.

Ideally, community groups should be involved in designing programs and environments in order to provide the best opportunities for physical activity. Table 5.2 lists goals for community physical activity programs and guidelines for their achievement adapted from Guidelines for a Comprehensive Program to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity (Nutrition and Physical Activity Work Group, 2002).

Learn more about Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents.

More Excerpts From Physical Activity Interventions in Children and AdolescentsSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW